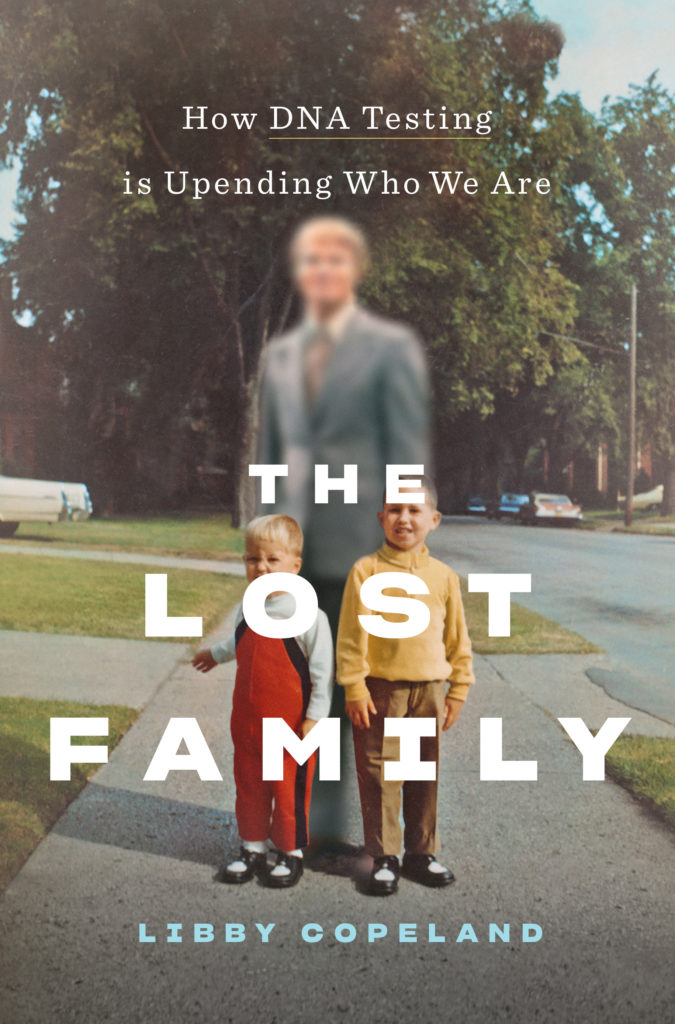

Home DNA testing for ancestry purposes has become a major cultural phenomenon. Award-winning journalist Libby Copeland explores it in her acclaimed book, The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are (Abrams, 2020). Now available in paperback, it is ideal for book clubs and the lively discussions that they provoke.

Close to 40 million Americans have been tested, and the number of people who experience surprising results is remarkably large. Libby Copeland estimates that at least 1 million testers have discovered either that the man they call Dad is not their genetic father or that they have a previously unknown half-sibling. A Pew Research Center study in 2019 found that more than a quarter of testers discovered a new “close relative” – a looser definition with a higher outcome. But because of the nature of family, revelations from a single test can impact many people, including those who haven’t tested.

Home DNA tests have altered our understanding of family and our conceptions of privacy. They have enabled “cold case” murders to be solved, while raising ethical questions of how the test results are to be used. They are changing the future of healthcare by building genetic databases that can be used to develop new pharmaceuticals. They have impacted many communities, including adoptees, the donor-conceived, and those who didn’t start out with questions about their families – but found questions posed by their DNA results.

In The Lost Family, Libby Copeland explores the culture of genealogy, the science of DNA, and the business of companies like Ancestry and 23andMe, all while tracing the story of one woman, her unusual results, and a relentless methodical drive for answers that becomes a thoroughly modern genetic detective story. The Washington Post says The Lost Family “reads like an Agatha Christie mystery” and “wrestles with some of the biggest questions in life: Who are we? What is family? Are we defined by nature, nurture or both?” The New York Times writes, “Before You Spit in That Vial, Read This Book.”

Proposed Book Club Discussion Topics

- Have you or others you know discovered unknown relatives through home DNA testing? What was the response? How do you think you would respond? Based on Libby Copeland’s research and insights, what do you think determines how people respond?

- Libby Copeland explores how DNA revelations can alter one’s perception of extended family. How might a change in whether someone is biologically related to you affect your definition of family?

- In some cases, after a surprising discovery, genetic kin embrace a newfound family member; in other cases, they do not. Which cases described by Libby Copeland moved you most? With which ones could you most easily identify?

- Home DNA testing is creating a collision of family narratives and family history – exposing truths that may not align with the stories that families have long told. Is it good for those truths to be told or better for the narratives to be left intact?

- DNA testing is making possible historical reckonings with cultural inequities and revealing racial and ethnic makeup that may not have been previously known. How does that affect a nation too often divided by racial and ethnic categories? Does it offer the prospect of less division?

- Home DNA testing has reached a tipping point – with close to 40 million Americans tested – where it has implications for those who are tested and those who are not. If a close relative of yours has been tested, then much of your genetic data is essentially in the database. How do you feel about that? Is that an invasion of your own privacy?

- Libby Copeland writes about a fundamental sociological shift – in that adoptions and donor-conceptions are no longer private. How do you feel about that? Is it better for adoptees and those who are donor-conceived to know their biological families, or unfair to those who counted on privacy?

- Home DNA test results solved the “cold case” serial murders of the Golden State Killer. On the one hand, law enforcement prevailed, and the victims’ families received closure; on the other hand, ethical issues were raised about the use of data collected for one purpose and used for another. How do you feel about that? Was the right balance struck?

- The countless difficult conversations and hard-won reconciliations happening across America suggest that the age of DNA testing may ultimately be moving us toward a more expansive and inclusive understanding of family. Do you think that is the case?